Z F Vratislav Brabenec is the author of much of the lyrics for the group Plastic People of the Universe. He also edited, for example, texts from the Old and New Testaments and texts by Ladislav Klíma. He collaborated with you on his book Legends and Lines.

F S Vratislav’s writing is great. There is a lot of lived wisdom and humor in it. Vratislav and Richard Pecha, who publishes his texts at the Vršovice 2016 publishing house, wanted me to create eight drawings, but I made about 40 to choose from. In the end, they used almost all of them. Often they just touch on the text, forming a funny connection with it. This is how we proceeded, for example, in the poetry anthology Kaloty by the B. K. S. group (acronym for “The End of the World is Coming”), published in Revolver Revue. I made a bunch of proposals, which we then assigned to the poems as we saw fit. In the book The Great Guardian by the Commander of the Order of the Green Ladybird, Jiří Olič, I was just given defined thematic areas – about actors, jazz, firefighters, Native Americans, teachers, etc. Z F You have also participated in bibliophile editions.

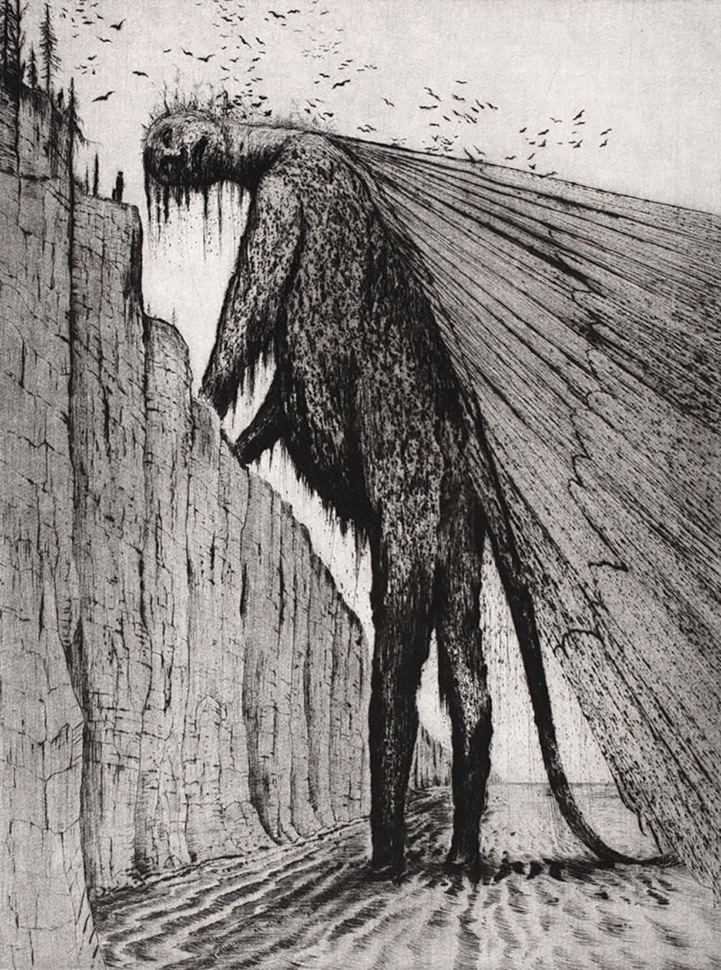

F S The bibliophile editions are a continuation of the work on the original prints. A few years ago, I returned to this kind of graphic art after taking a break from it for 20 years, and I made 16 dry points in six months. I could have continued, but something else attracted my attention. Endless, enticing horizons open up everywhere.

Z F I will go back to Jostein Gaarder’s Frog Castle, which you created using unusual collages. Was that because of the nature of the book?

F S The Norwegian writer Jostein Gaarder wrote the bestseller Sophie’s World: A Novel about the History of Philosophy for teenagers, for which I made the cover. The Frog Castle is a surreal story with perfect knowledge of the child’s soul. The mixed media with collages was a suitable technique. At that time I was intensely involved in the beauty of autumn leaves, which were reflected both in my noncommissioned art and in this book. There is a scan of a frog’s real skin on the cover, and inside the book are the pancakes that are talked about there.

Z F From your illustrations it is obvious that you have read the books and subordinated the character of the illustrations accordingly.

F S Yes – for example, for The Borrowers by Mary Norton, a book set in Victorian England, I learned to do cross-hatching with a pen for black and white illustrations in order to approximate the techniques used in those days. It’s like when responsible actors prepare for their roles.

Z F I should probably have asked this question at the beginning, but I believe it has its place at the end as well. In your illustrations, you use a number of artistic techniques. Which are they? Which do you prefer?

F S I opt for a technique based on the topic and nature of the illustrations. The most common is probably watercolor in combination with crayons. Sometimes it’s totally mixed media, as in Sandburg’s Rootabaga Stories, where I used everything – watercolor, oil, pencil, crayon and collage. In Šiktanc’s Candlestick Castle it’s watercolor, charcoal and oil. Or just the charcoal wash technique, such as for his Royal Fairy Tales. Black and white illustrations, on the other hand, can be done in pen and ink, pencil, or ink wash. Or maybe using frottage, like in Momo. The original technique of scurography, where the negative is drawn in pencil on tracing paper and subsequently developed like a photograph, was appropriate for The Brothers Lionheart.

Z F So far I have not mentioned your diaries, excerpts from which have also been published. In fact, they are contemporary illustrations of your life. Do you still keep a diary?

F S I started keeping diaries, of which there are currently at least 90, in the 1990s, starting with the Venetian Diary at the 1993 Venice Biennale. However, my very first diary is from 1992, when at the Expo in Seville, Michal Cihlář and I found a notebook that we divided in half between the two of us. He was constantly writing down something at the time, and because he got on my nerves by doing that, I started doing the same.

The travel diaries are, of course, more artistically attractive, full of collected materials and experiences. The everyday ones are practical, because by the end of the week you don’t remember what you were doing anymore, let alone 10 years afterwards. What I am working on is also reflected there. The enthusiasm and disappointment. If someone makes me angry, I give them a piece of my mind there. What I like the most, though, is how the cover of these little books becomes gradually decorated and patinated over the course of about a month.

Other illustrations of my life are the photos taken with my favorite little Lumix camera. However, I try not to take too many of them.

Z F The exhibition begins with your early paintings, on the threshold between childhood and adulthood, and ends with examples of your current work. Have you ever published your beginning works before?

F S Most artists do not do this, so as not to “reveal themselves”. I, on the contrary, like best to see the marginal or the “pajama” drawings of the masters, not the artworks that just reproduce their “brand”, which can be recognized by any yokel. Of course, I have selected the palatable ones. Under the motto “the master is searching for himself”, I needed to deal with different styles. These works were exhibited in the 1970s at the exhibitions in our back room at home, and there are hand-made samizdat catalogues accompanying them. I have to say that it is only when I see them together that I realize the connections between them.

My current work represents my passion of the last three years – paintings made mostly using natural pigments that I collected in the countryside. It will be interesting to see my different approach in comparison with that of Jan Jedlička, who is exhibiting in the Municipal Library and has been intensively involved in this since the 1970s.

Translated by Vladimíra Šefranka Žáková