I saw the best minds of my generation…

Besides being introduced to his craft by the greatest authorities of the European photographic school, one specific moment in Xiao Quan’s life formed an important initial impulse to begin photographing. Xiao Quan recalls how strongly he was influenced by the portrait of the American poet Ezra Pound, shot in 1963 in Venice by the Armenian photographer Yousuf Karsh and reproduced in the late 1980s in China’s literary magazine Image Puzzle (象罔, Xiangwang). Coincidentally, Pound was an important linguist and expert in Chinese poetry. If a photograph of Pound was Xiao Quan’s punctum in the Barthesian sense, a true trigger moment, we may consider the possibility that Pound himself unconsciously took on this role as catalyst. Pound is, among other things, the author of Cathay (1915), a collection of loosely translated ancient Chinese poetry, and also the editor and co-author of Ernest F. Fenollosa’s theoretical essay The Chinese Written Character As a Medium for Poetry (1920), written in 1908 but not published until after its author’s death. In this essay, Fenollosa, curator of the Asian collection at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, understood Chinese poetry and its graphic poetics as a calligraphic ideogram.

In this way, we return to the thesis that a photograph is an encoded message from its creator that must deciphered just as we do with written texts, which in Chinese are additionally written using symbols. This configuration of verbal and visual expression in photography recalls Pound’s ideogrammic method founded on the arrangement of images into a single expression. But back to the photograph of Pound. When he saw this photograph of the elegant-looking Ezra Pound with a hat and walking cane, the young Xiao Quan decided that he is going to capture “the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness.”

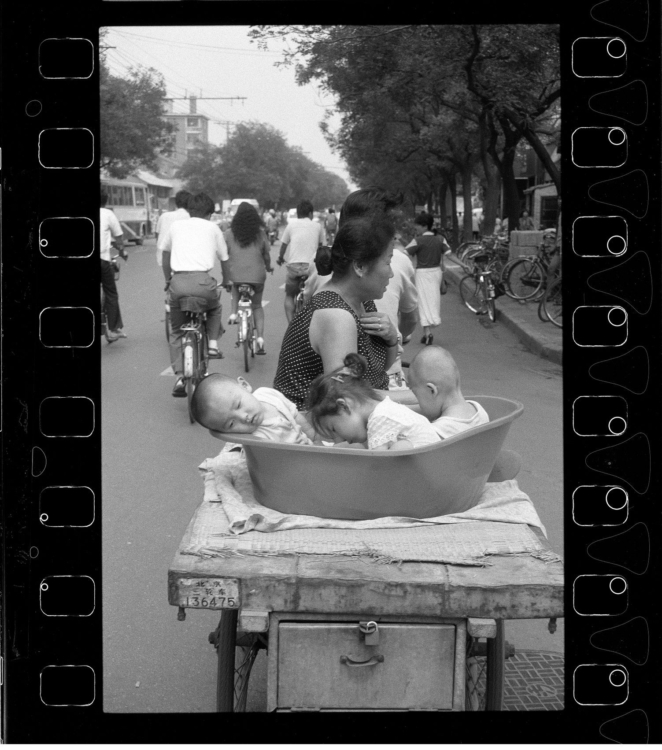

From the ashes of the Cultural Revolution There followed the series Our Generation (我们这一代), first published in the aforementioned Image Puzzle and later, in 1991, in book form, thanks to which Xiao Quan became known at home. This series depicts members of the avant-garde culture scene that emerged from the ashes of the Cultural Revolution. The photographs were taken between 1986 and 1996, often before many of their subjects became famous. In 1986, Xiao Quan photographed poets energetically reciting their works during the China Star Poetry Festival in his hometown of Chengdu. In 1990, he recorded a rock concert by the musician Cui Jian, whose songs were a source of optimism and excitement and a driving force in the life of the country’s younger generations. An important milestone for Chinese culture was the year 1992, when the first art biennial was held in Canton (Guangdong Art Biennale), thus opening the door for Chinese art to enter the international art market. When, soon thereafter, Wang Guangyi’s painting Great Criticism appeared on the cover of Flash Art, the existence of contemporary art in the People’s Republic of China was legitimized.

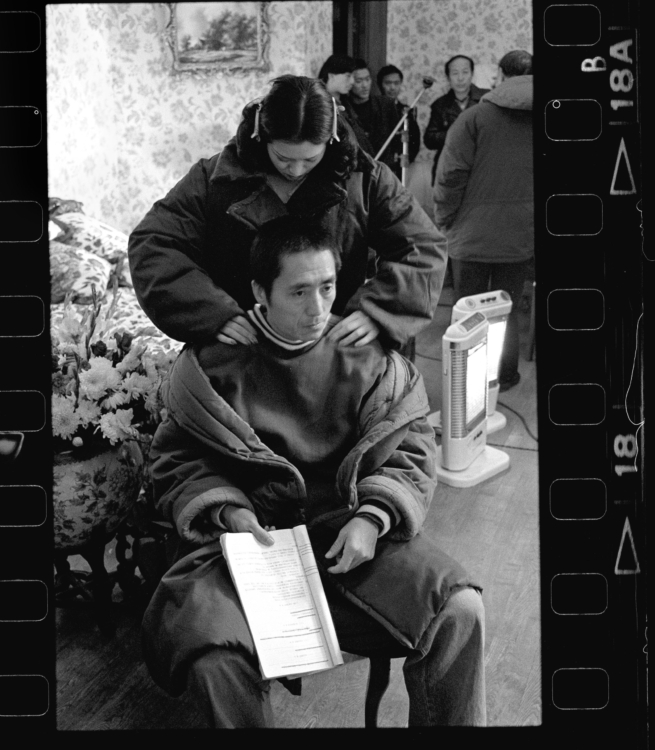

In 1994, Xiao Quan covered another area of culture outside of art and literature when he photographed the actress Gong Li while she was shooting the film Shanghai Triad with the internationally acclaimed director Zhang Yimou. Czech viewers may recall some of his photographs of the painters Wang Guangyi and Zhang Xiaogang from the exhibition The Reunion of Poetry and Philosophy, organized in 2018 at Prague City Gallery’s Stone Bell House by Xiao Quan’s friend, the renowned curator Lü Peng, who is also behind the upcoming exhibition in Prague. Peng has a long history of presenting underground Chinese art through exhibitions and by compiling a new and previously lacking canon of twentieth- century Chinese art.

Opening to the world – Throwing back the curtain

Like Lü Nan (呂楠, 1962), Zhang Haier (张海儿, 1957), and Han Lei (韩磊, 1967), Xiao Quan is a pioneer who helped Chinese photography undergo rapid development from documentary to conceptual and staged photography. This form of photography is very popular in China today, and along with digital post-production it is one of the most used media on the art scene, as Czech audiences may have noted thanks to Petr Nedoma’s 2003 exhibition A Strange Heaven.

Photography was an important tool for the emerging conceptualists and performance artists who in the early 1990s experimented in artists’ colonies with what for them were new or recently discovered forms of 20th- century modern art imported from the West. These artists did not want to be primarily photographers, however, and used the medium only as a tool. The photographic act was always more important than the photograph itself, which does not have as long a tradition as it does in Europe or America. Truly modern Chinese photography first appeared in the late 1970s, when documentary photography, despite continuing to bow to political demands, also took on a critical tone. Up until this point, the medium had been used by the political power structures to manipulate society and had functioned as a historical resource (though one subject to frequent censorship). The turning point came in 1979, when Beijing’s Zhongshan Park hosted the exhibition Nature, Society, and Man. This first-ever group exhibition of amateur photographers was organized by the April Photography Society (四月影会, Siyue ying hui), an independent art group active in the capital in 1979–1981 that sought to move away from socialistic realism and to return to autonomous photography. Social criticism in photography was slowly transformed into a search for new traditions that went hand in hand with the arrival of humanistic and existential works of literature from the West.

In 1979, Deng Xiaoping announced the reform known as the Four Modernizations, with its emphasis on opening up to the world. These changes enabled China to transform itself into a modern economic power in which shortages were replaced by opulence. The 1980s were a decade of rebirth, a time when society (not just in political circles) worked to lift up a country that had been ravaged by the earlier Maoist experiments. For intellectuals, this period was a renaissance, as they emerged from isolation and began to find inspiration from European and American art, literature, and above all existentialist philosophy.

Artistic experimentation, though still in the form of underground (dixia) art, flourished in music, film, literature, and visual art. For a brief period, China was home to freedom of expression and extravagant subcultures. The atmosphere differed significantly from that of the previous decade, when the entire country was still recovering from the dire consequences of the Cultural Revolution (1966–1967). Although many active participants in cultural life were inspired by Western artists and thinkers, it was not always easy to get one’s hands on the source material. In the period from 1970 to 1980, when Xiao Quan was beginning to take an interest in photography, it was extremely difficult to find any reference works on photographic theory or to learn anything about the Western art world. In this context, an important role was played by underground magazines and mimeographed, hand-bound samizdat editions of just a dozen or so copies passed from person to person – examples include the literary magazine Image Puzzle, Today (今天, Jintian) and many others.

Somewhat later, a similar role was played in China’s underground art scene by Ai Weiwei’s trilogy Black Cover Book (1994), White Cover Book (1995), and Grey Cover Book (1998). Thanks to their author’s American experience, Weiwei’s publications could introduce their readers to books and critical texts by important international representatives of conceptual and performance art.