Where Does He Fit? Karel Otto Hrubý – A Hard Nut to Crack Josef Chuchma

A charismatic jack of all trades, magician straddling the line between amateur and professional photography, balancing between craft and artistic ambition. Josef Chuchma deems that K. O. Hrubý’s voluminous, varied and erratic work could be gathered into different exhibitions or series of books. An attempt to grasp the legacy of Karel Otto Hrubý can be seen at the House of Photography.

Although Karel Otto Hrubý was a fixture of Czech photography and the local photographic scene for decades, his work was only fully appreciated in 2017, when one hundred and one years had passed since his birth. At that time, the House of Arts in Brno prepared an exhibition and also contributed to the publication of a monograph summarising the creative, organisational and educational contribution of “K. O. H.”, the acronym by which the artist was well known in his day. In March 2018, the retrospective came to an end, and, almost exactly five years later to the day, its Prague version was launched, with Lukáš Bártl, Antonín Dufek and Jana Vránová as the main curators. They took part in the Brno premiere, but this year is not a reproduction, a simple reprise, but a selection adapted for the two-storey premises of GHMP’s House of Photography in Revoluční Street.

On Many Fronts

Karel Otto Hrubý was active as a photographer, teacher, lecturer, curator, organiser, publicist and critic. Within the history of Czech photography, perhaps only Vladimír Birgus (b. 1954), who for more than four decades has managed to simultaneously carry out most of the activities in which Karel Otto Hrubý was fully immersed, can match him. Hrubý was born in Vienna in 1916, but graduated from the grammar school in Znojmo and went to Prague to study law at Charles University, although he did not complete his studies due to the forced closure of universities after the Nazi occupation. He moved to Brno and earned a living as a jazz musician until he was pressed into forced labour in 1941. Simultaneously – and with increasing seriousness! – he also took up photography, which became his main occupation after the war. He first worked at the Rovnost daily newspaper, then as a cinematographer for documentary and advertising films, as a theatre photographer and, in 1951, he was again employed in the press – this time at the Prague-based Květy magazine. But Hrubý’s stay in the capital did not last long. The very next year he took the opportunity to teach photography at the Brno Secondary School of Arts and Crafts. He worked there until 1977 when he suffered a heart attack. He recovered, moved to Senotín in South Bohemia, slowed down his hectic pace, turned to painting and “forgot” about photography and the activities surrounding it in which he excelled. He died in 1998.

In his monograph Karel Otto Hrubý – Photographer, Educator, Theorist (2017), curator and theorist Jiří Pátek notes that after 1978, “not a single line” can be found from this industrious writer, who for twenty years wrote reviews for the monthly Československá fotografie (Czechoslovak Photography). According to Pátek, “he was able to express himself in a lively language, he was witty, gracious and, when appropriate, ironic”. On a personal note: as the son of a father who used to regularly buy the magazine, read it and underline passages that were important to him, I remember seeing the name of Karel Otto Hrubý for the first time when I also started reading the Czechoslovak Photography magazine in my younger years – many of the passages my had father underlined were found in K. O. H.’s articles.

A True Son of His Era

According to surviving witnesses, Karel Otto Hrubý had personal charisma, was a skilful communicator, and could almost magically straddle the line between amateur and professional photography, which in Czechoslovakia was otherwise a specific divide – on the one hand, professionals in the media or advertising, plus a few artistic photographers, and on the other hand, amateurs, many of whom did not go beyond the level of “hobby art”. But at the same time, there were also artists in this category who did not make a living from photography, but “as a pastime” they were constantly focused on creating their work, which is more valuable today than the purposive products of the professionals of the time (see the work of Bohdan Holomíček, Viktor Kolář, Gustav Aulehla and some other “amateurs”).

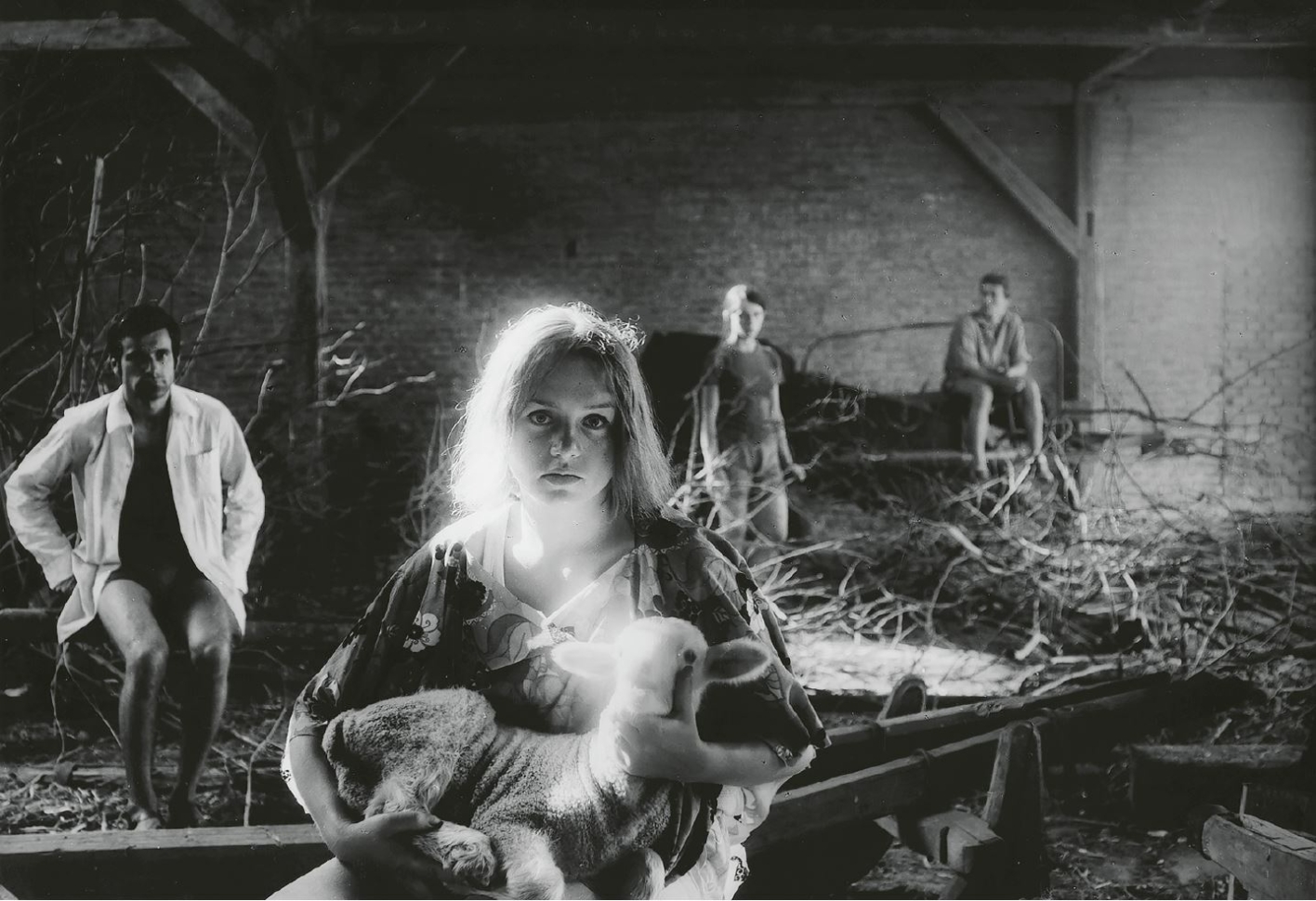

Browsing through the photographic works in the above-mentioned book, Karel Otto Hrubý – Photographer, Educator, Theorist, one cannot help but notice that even “in practice” Hrubý maintained a balance between skilled craft and fine art photography with artistic ambitions. Some of his pictures are prime examples of socialist realism. When the most horrific period of Stalinism was over, some artists, in Czech poetry as well as in photography, Hrubý among them, turned to de-ideologised everyday themes and to civilism. Karel Otto Hrubý responded to yet another call of the times in the sixties when he created, among other things, staged photographs; in addition to these, he also created around fifty collages. On top of that, he also liked to travel and take pictures of rural and urban landscapes; in fact, together with Antonín Hinšt, he published an educational book, Krajinářská fotografie (Landscape Photography), in 1974. Karel Otto Hrubý also independently prepared two publications focused on two specific locations in the early 1960s: Brno and Vysočinou po řece Jihlavě.

His work is voluminous, varied and – erratic, or one could say – very much tied to the era in which it originated. It could be gathered into quite a different exhibition or series of books. One of them could comprise socialist realist studies of scenes from factories and villages. Another could be civilist, featuring snapshots. Yet another grouping could be made of landscape works and artoriented work. All of them would represent Karel Otto Hrubý, but always in a reduced way; each would never “truly” be all of him. For there is no “true” core to the work of Karel Otto Hrubý. Therefore, anyone wanting to provide a relatively truthful account of him is faced with the difficult task of interpretive selection, which should not ignore the selfserving features in the artist’s work, and, at the same time, his more or less successful efforts to keep his creative expression up to the standards of his time.

One basic feature arches over all this – Hrubý was a traditionalist. He worked with black-and-white material, he paid attention to quality technical processing and to the “golden rules” of composition. He in no way questioned the representational fidelity of the photographic medium; he did not work with a concept in which photographs refer to a certain phenomenon with varying degrees of sophistication. The above- quoted Jiří Pátek aptly reminds us that in his reviews, K. O. H. had a negative attitude towards two Brno exhibitions (1969, 1975) by Jan Svoboda, now considered something of a classic, whose minimalist, (self-)reflective and philosophical still lifes and photographs of the most ordinary objects, works whose grey tonality was inspired by Cézanne’s theory of tonal colour, Hrubý was unable to accept. He described them as “grey, pushed, pulled or unevenly lit enlargements”.

Presenting the work of Karel Otto Hrubý is therefore a challenge. How the curators have approached his legacy in 2023 can be discovered at the House of Photography until 21 May.