Q Your current exhibition is called Silence, Torso, the Present. Can you talk us through this title and your thinking in preparing the exhibition?

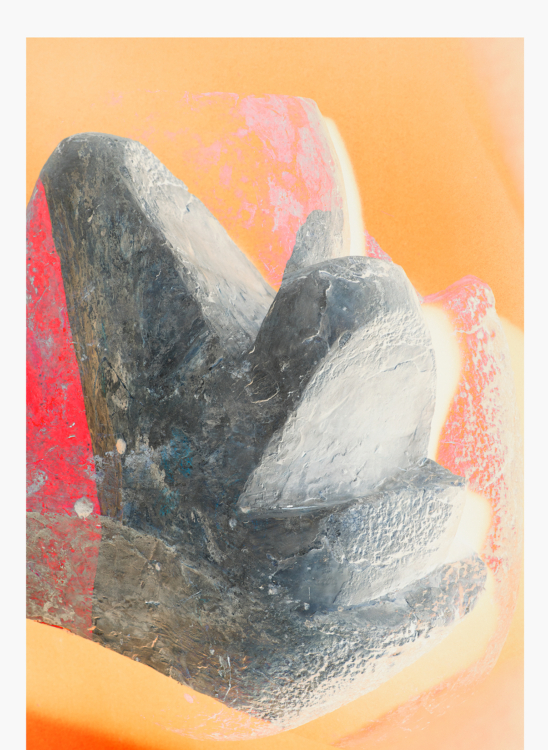

J T In recent years, my work has focused on the analysis of the birth of a work of art. It’s rather a subjective self-questioning. But I am interested in consciousness as such and how it functions within the creative process. I first thematised this in my series Consciousness as a Basic Assumption. In Silence, Torso, the Present, I am looking for forms of new representation, albeit through traditional photographic processes. Unlike painting, for example, in photography the immediacy and possibility of using the energy of gesture is very limited. I try to work in such a way that it is present in the image.

Q What appeals to you most about Hana Wichterlová’s work and how did you first encounter it? Is there anything specific about “female” sculpture in your opinion? I’m thinking about the inspiration from the work of Alina Szapocznikow or the spatial sculpture of Katarzyna Kobro.

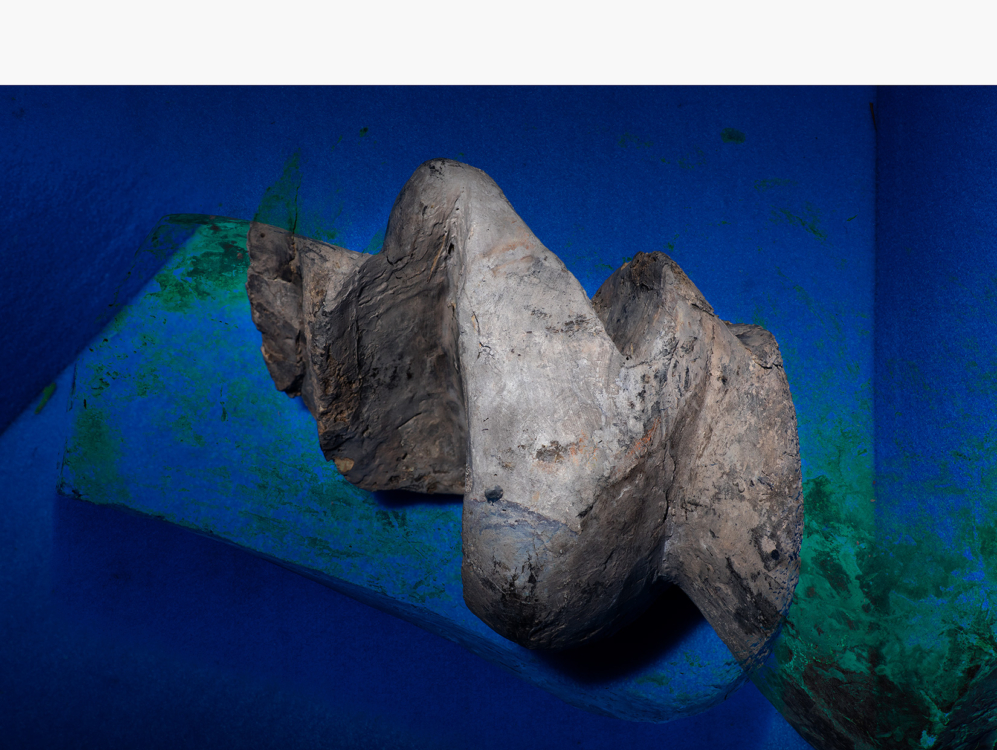

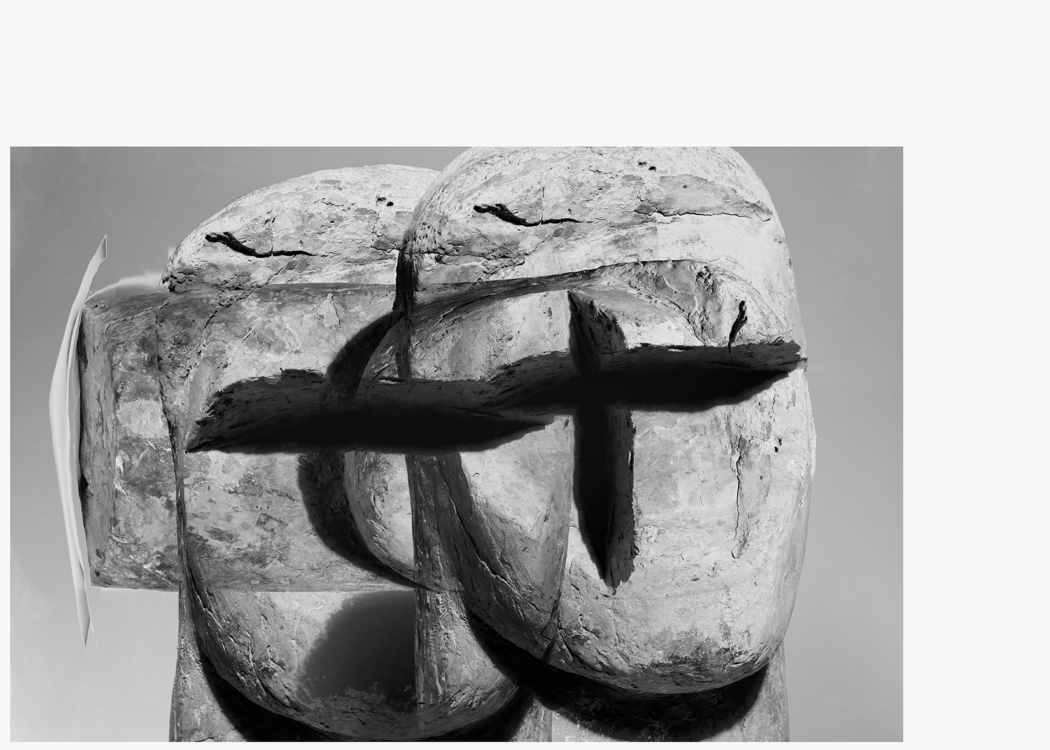

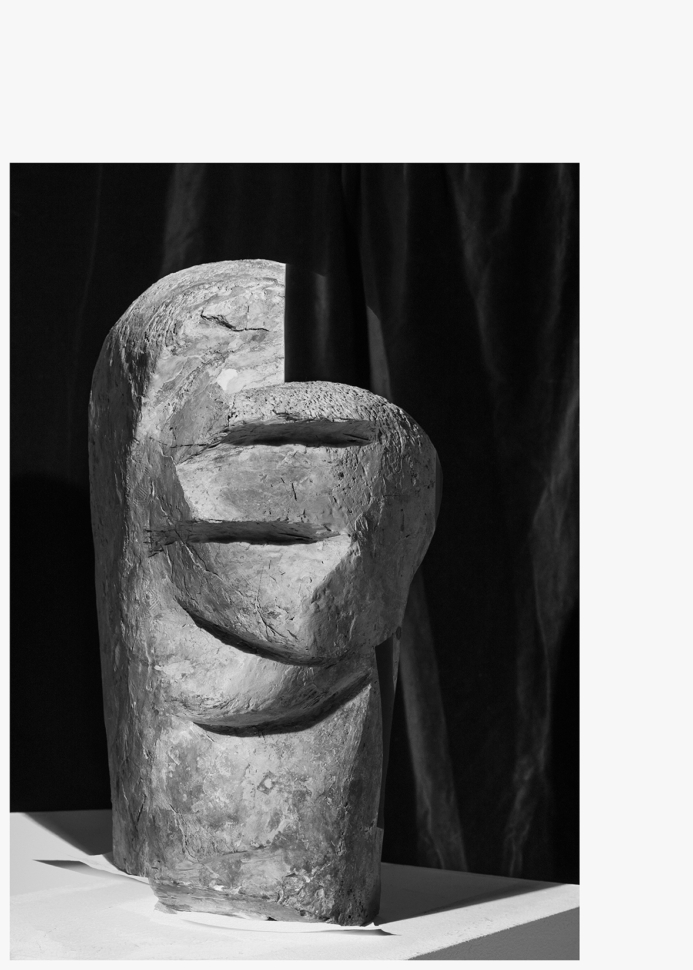

J T It’s based on a feeling. I subconsciously perceive certain aspects of their work that are close to me. But I can’t explain why that is. In the case of Kobro and Szapocznikow, it was through photographic reproductions in a professional publication. I only encountered Hana Wichterlová’s work at an exhibition devoted to Josef Sudek’s photographic reproductions. It was a powerful experience for me. At first I had no idea that the authors of these works were women. When I first encounter a work, I don’t consider it important who created it. I don’t see authorship as essential to the meaning of the work. In the larger context, however, I am obviously interested in the author. If I were to be more specific, what captivated me about Wichterlová’s sculptures is their internal integrity and how they are anchored and focused. From her work, which is not very extensive, I sense a kind of singular vision that is timeless in many ways.

Q In the future, you would like to contribute an artistic intervention to Hana Wichterlová’s studio; what would it look like? Would it be similar to the installation at the House of Photography? Can you please describe your plan? You are also interfering with the exhibition panels as an artist…

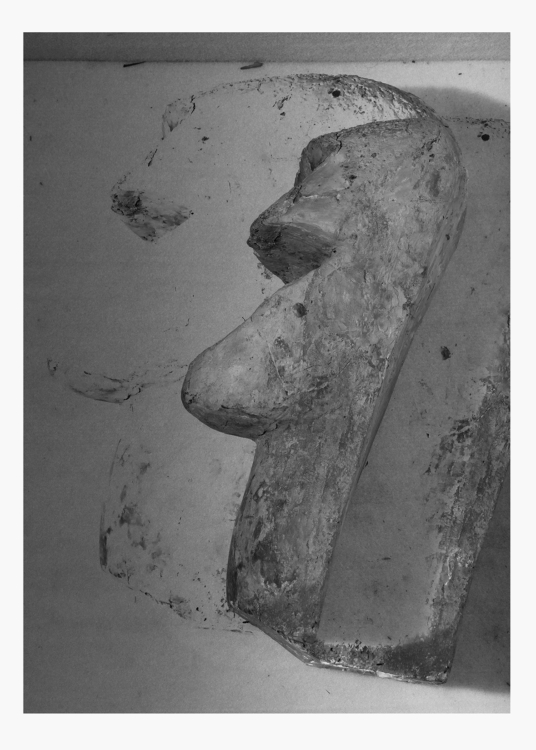

J T I think of the spatial intervention in the House of Photography more as being autonomous objects whose dimensions I adapted to the gallery space. Similarly to photograms or exhibited photographs, the installations are created by layering individual images taken from different angles. I transfer shapes based on Hanna Wichterlová’s sculptures onto plasterboard walls. I then cut them up and layer them on top of each other. This creates an autonomous sculpture, but it carries “Wichterlová’s DNA”, a kind of original information from the shapes of the sculptor’s works. Perhaps in the future, a spatial installation based on an analogous principle will be created in Hana Wichterlová’s studio.

Q Do you enjoy your work as a teacher? At what institutions have you taught? And how do you remember the photographer Pavel Štecha?

J T I only have positive memories of him. Pavel Štecha was an open type of person and a teacher, a kind of role model. During my studies, I started to move towards non-commissioned art quite early on. That was a bit outside the context of the studio at that time; it profiled itself more as being utilitarian. Personally, I see teaching primarily as a commitment and a great responsibility. Of course, today’s generation of students is different in many ways. After my experience of teaching at the Scholastika art college and at FAMU, where I headed the studio of post-conceptual photography for several years, I now run the studio of applied photography at the University of Ústí nad Labem together with Václav Kopecký. It’s a great new experience that allows us to pursue a new vision and lead students to greater flexibility and interdisciplinary collaboration. But that would be a topic for a separate conversation.

Jiří Thýn (* 1977) graduated from the Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design (Studio of Photography, prof. Pavel Štecha) and also had an internship at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague (Studio of Painting II / school of Vladimír Skrepl). He took part in several scholarship programmes abroad, for example, a residency in the Photography Studio at TAIK University in Helsinki, PROGR in Bern and FONCA in Mexico City. He often combines his photographic work with installations, paintings, texts and videos. He deals with the medium of photography itself and its overlaps, as well as with other themes, such as space

and composition, and combines traditional photographic techniques with a contemporary post-conceptual approach. He also thematises and explores various photographic techniques, such as photograms. He worked as the head of the Studio of Post-Conceptual Photography at FAMU in Prague and now teaches at Scholastika college and at the Faculty of Art and Design of Jan Evangelista Purkyně University in Ústí nad Labem. He is represented by the hunt kastner gallery. He reached the finals of the Jindřich Chalupecký Award in 2011 and 2012.