There are music labels whose graphic design quickly makes it clear that they are not only concerned with music, that the publisher’s conception is informed by ideas, feelings and cultural societies which, along with the music, can be projected into the art form, into the accompanying texts; and even grow into a catalogue as a story of interrelated references. Such labels have the potential to affect the wider cultural public through their literary and film references and through their ties to traditional cultures as well as to avant-garde movements. Jan Jedlička became part of this enterprise when he met producer Manfred Eicher in the late 1980s.

The Most Beautiful Sound Next to Silence

Eicher has been managing ECM Records (Editions of Contemporary Music) since 1969. To briefly characterise this groundbreaking label is to say that it helped to find the identity of European jazz and very quickly went “above genres”, combining jazz improvisation with elements of chamber music and traditional cultures. It provided space to key American personalities (such as Chick Corea and Keith Jarrett), discovered for the world a number of great names (Jan Garbarek, Pat Metheny, Bill Frisell…). In the early 1980s, it added classical music to its portfolio: to this day, the great minimalists Meredith Monk and Arvo Pärt premiere their music in the classical music series called the ECM New Series.

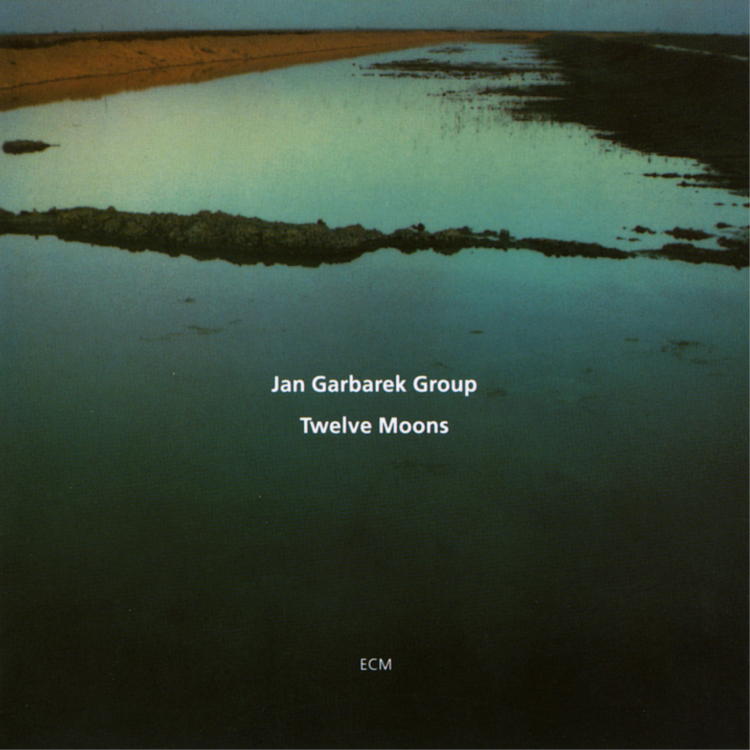

It quickly became clear that the visual art side of the label’s music media would be both bold and connected, conceptual in fact. Designer Barbara Wojirsch made her mark on the label with her use of drawings and typeface, her exuberant style sometimes showing the inspiration of Cy Twombly; Dieter Rahm, another of their leading graphic artists, also contributes photographs that almost never have a direct connection with the musical content. “There’s always something mysterious about a landscape without a human,” Eicher says of the scenes he chooses for his covers.

The graphic side of ECM, with its decades of variation, also has its critics: the purity and aestheticism are said to distract from concrete reality. But the label, which has never lost its independence during the fifty years of its existence, takes care to move in the interspaces rather than at the poles. The exhibition projects and book monographs of ECM (Windfall Light: The Visual Language of ECM or Horizons Touched: The Music of ECM) draw on visuals easily, extensively and convincingly.

A Shark’s Fin of Light

When Jan Jedlička was working on his film Echo Vocis Imago in the late 1980s, he very much wanted Arvo Pärt’s music to be played in it. He actually made a trip to Berlin and rang the doorbell of this Estonian exile, who was experiencing the first decade of his global fame at the time. Pärt looked at Jedlička from behind his hermit’s beard and said after a while: “You can come in.”

Jan Jedlička showed him some of his work: photographs, paintings and drawings, which he would leave his Swiss home to create, mainly in Maremma, a region in southern Tuscany. Pärt studied them intently, but frowned at the mention of film music: Ich bin kein Stravinsky, I don’t write film music to order! He reportedly said. However, he declared that he had to think it over and with those words he parted from his Czech colleague. At his next meeting with Manfred Eicher, he showed the producer and moving spirit of ECM Jedlička’s books and reproductions. By doing so, he did more for Jedlička than if he had consented to compose the film music.

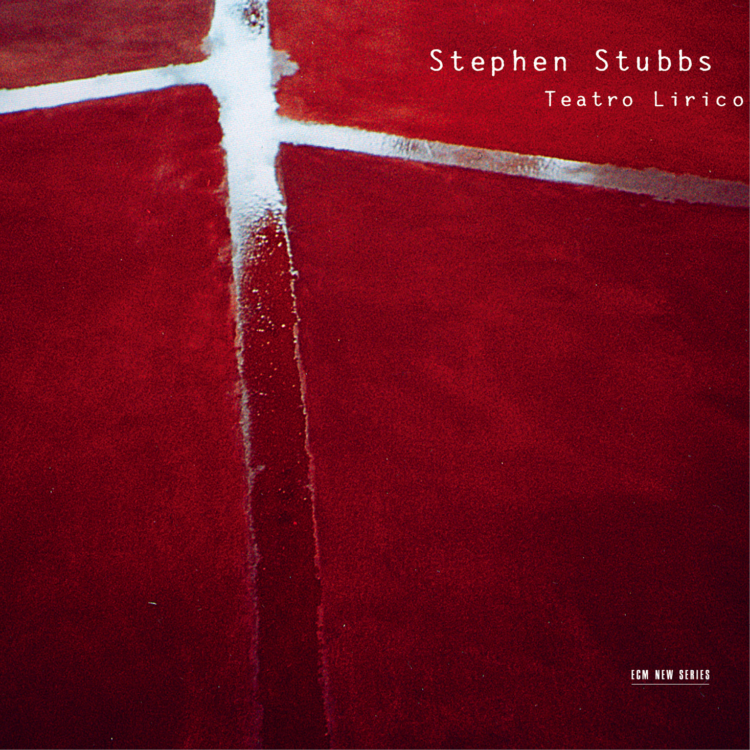

Eicher, who approves the artistic appearance of each ECM album, soon contacted Jedlička. First, he immediately ordered ten or fifteen copies of his books from him (which he then distributed to “his” musicians) and he was also interested in cooperating with Jedlička. On the first title they made jointly, there is a “Shark’s Fin of Light”, a triangular light shape on the shadowed wall of a house in Maremma: originally, it is a photodocumentary snapshot from the film Echo Vocis Imago in which Jedlička records the movement of light on a wall using time-lapse photography. The black- and-white scene, satisfactorily empty and referring to something outside itself, fits into Manfred Eicher’s vision: reduction, an abstract constellation that can refer to both micro- and macro-levels, the landscape as “the inner landscape” (this is Eicher’s own expression). The photo was used on the cover of viola concerts by Alfred Schnittke and a Georgian composer, Giya Kancheli, released in 1992.

Basilica

The cooperation had begun. It lasts to this day. Jan Jedlička and Manfred Eicher meet now and again; Eicher looks at his new work and makes his choice. It is characteristic of the ECM concept that photographs, paintings and drawings are equally usable. Exported stills from films are also used: for example, this is how the disturbing and solemn scene of grass-burning froze into a photo cover for the album From The Green Hill by trumpeter Tomasz Stańko.

Jan Jedlička himself, who is satisfied with the collaboration, does not influence which of his works Eicher chooses and with which music he connects it. For the Horizons Touched: The Music of ECM book monograph, he made this comment: “I came to realize and respect the fact that ECM is a creation of Manfred Eicher’s personality, his intuition. The way he looks at pictures and listens to music. This makes me always very curious to see what he has chosen.” Sometimes there is closer communication: during the publication of Leoš Janáček’s complete piano works, performed by András Schiff, the producer asked the artist to provide photographs of the Czech landscape. Inside the booklet, there is thus a series of pictures that Jan Jedlička took as a student in 1963, before emigrating. Photographs from another time and place resonate with the title of the whole album (after Janáček’s composition) A Recollection, i.e. a Memory.

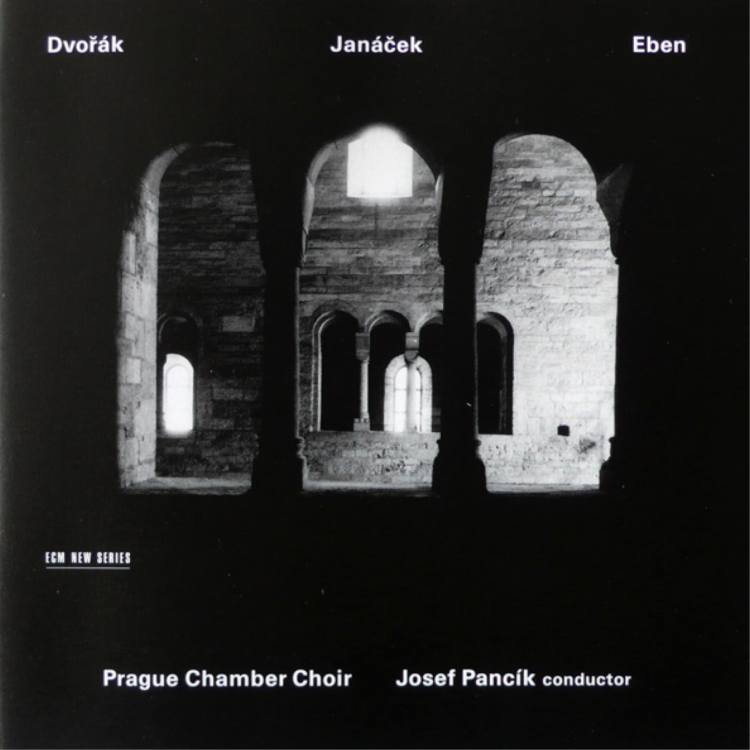

The photo study of the architecture of St. George’s Basilica at Prague Castle, originating from Jedlička’s Basilica series, ended up on one of the few truly Czech ECM titles: on a recording by the Prague Philharmonic Choir with choir master Josef Pančík (the repertoire consisting of music by Dvořák, Suk and Eben). This painting evokes the mid-1990s, when Jan Jedlička was first being more widely discovered in the Czech Republic. In addition to exhibiting his works at Prague Castle (at that time seemingly self-evidently open to culture and the public) for his project he also photographed and filmed places where the light falls which are precisely oriented by the old architecture of St. George’s Basilica.