Milena Dopitová

On the Border Between Public and Intimate

KF In 1989, you co-founded the Monday Art Group. In what atmosphere was it at the time?

MD In communist Czechoslovakia, there were only three schools focused on non-commissioned art – two in Prague, one in Bratislava. Thus, the interest of applicants exceeded the supply multiple times, and priority was given to those with the “correct” political background. Many of us applied repeatedly, and thus, in my year of studies, there were people who did not let themselves get discouraged because they wanted nothing more but to be accepted. During the first year, we became familiar with the school environment and got involved in all the activities that were already gathering pace in the pre-revolutionary era. It was in that period that we founded the Monday Group. We spent a lot of time together looking for ways how and reasons why to make art. In retrospect, I realize with some nostalgia that it was a happy time of beginnings as a student living under totalitarian conditions. Because these conditions had a share in the formation of the group and, consequently, in everything that started this encounter.

KF But then came the revolution.

MD All these events caught us on the move and we took them for granted to some extent. Unlike our parents, who experienced the occupation in 1968, we felt that things could not have turned out any other way. Today, I see it as a great good fortune that I was able to be there and experience it. Anyone who lived and worked during that time finds it increasingly difficult, as time passes, to find words to describe it without looking like some kind of a dreamer. It was an amazing euphoria; in addition to other reasons also due to the fact that we could change history also on behalf of our parents.

KF What did the first free years, the beginning of the 1990s, mean to you?

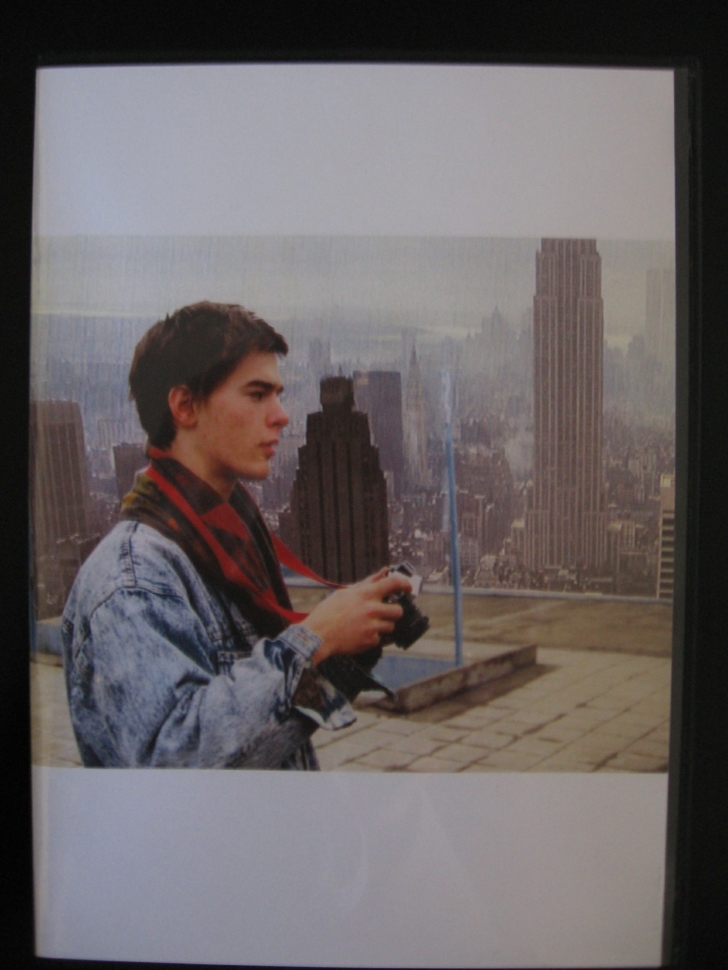

MD I guess it was mainly the open space for work, the possibility to travel and to feel freedom not only in myself but also in my surroundings. The revolution started the interest in Czech art, important figures were coming here and involved us in international projects. It was a fast time of many exhibitions, one work following another and we did not realize that it did not have to be like that forever. Suddenly, I could represent our country at biennales in Sydney, São Paulo, Aperto, Gwangju, exhibit in New York, London and Berlin. Often while I was still a student. So for me the 1990s were mainly work, work, work, but so joyful!

KF You talk about abroad, but what were the exhibition opportunities like here in the Czech Republic?

MD Alongside state institutions, the private galleries such as MXM began to emerge. MXM quickly became, among other things, a centre of current discussions that shaped contemporary art, a meeting place for artists, theoreticians, philosophers… Above all, its curators Jana and Jiří Ševčík were really responsible for the implementation of many exhibition projects and theoretical publications in both the Czech and the international context. As far as public institutions are concerned, it was primarily the GHMP, led by curators Olga Malá and Karel Srp, who opened the doors of larger galleries to contemporary art in the 1990s.

KF Thanks to this, spaces like the Stone Bell House opened up to you…

MD The work of the 1990s was very much related to space: that’s just because many of us turned to installations, to objects, it was a new challenge. In 1997, I responded to a space in Baden Baden with the Not for Sale object – a lying figure eight symbolizing infinity. The abstract notion of volume, of quantity, was given shape, size and colour, i.e., a real form. At the same time, it was a large, three-metre long braided figure eight. At that time, we didn’t think at all about the practical questions of how to disassemble it or store it after the exhibition, we simply made objects for monumental spaces. Because we could! Because anything was possible – to combine media, to combine anything with anything else and to break any boundaries. As long as there was enough money for the project, nothing prevented the realization of any ideas.

KF And the themes?

MD For me, they have always been inextricably linked to life and atmosphere. The beginnings of the search followed the agenda of the Monday Group, whose credo was “Don’t neglect the little things and compulsory exercises”. Our relationship to the mundane, the ordinary and the everyday, was related to this. The social overlap was then translated by each of the members in their own way. One of our first exhibitions was called New Intimacy, and it was the movement on the border between the public and the intimate that was crucial for me for a long time. A lot was said about it in texts and articles about my work at the time, so I see it now as a bit of a marker of the 1990s. Today, I’m responding to a completely different period of time, with a completely different atmosphere. However, many of my works continue to have this level of meaning.