Koubová Walking Through Petříček Alice Koubová

Philosopher Alice Koubová walked through the exhibition Thinking Through Images curated by Jitka Hlaváčková and philosopher Miroslav Petříček. The result is a travelogue.

To get to the exhibition Thinking Through Images: Visual events by Miroslav Petříček, I go straight from a school where art is studied. I walk a distance of only two hundred metres, but to be able to trust the exhibition and its premise, namely that “art provokes a physical reaction which is the beginning of a process of thinking that depends on how much one opens oneself to the situation”, I actually have to try hard. I accept that this is a subjective starting point. I work at DAMU as a vice dean for science and research and one of my efforts is to nurture precisely this space of possible expansion of thinking through artistic experiences that are sensory, figurative, and often difficult to articulate or, on the contrary, more than clear. Artists are those who both create works of art and are exposed to works of art. One might thus assume that their own artistic work will be embodied in them as a physical thinking of otherness, empathy, self-transformation, and that also their teachers will be such thinkers par excellence.

In the field of art, an entire spectrum of ways to shape, share, and talk about singular models of the world has originated for this purpose: artistic research. Even Mirek Petříček describes artistic research as a suitable alternative to an overly logocentric science, because of its ability to build on the specific artistic experience and its way of exploring the world.

The second area that needs to be constantly thought about, reassessed, and addressed in an art school is the relational environment itself, the mechanism of power within the institution, the specific meaning of the phrase freedom of speech, the sense of otherness, sensitivity, openness, subversion, and the status quo.

In both areas, Petříček’s hopes that art will “make us think”, that it will “rid us of what we know” and help us “to adopt the point of view of someone else, to encounter another model of the world” get confronted with reality. Artistic research is alternately labelled as something we’ve been doing for decades and, moments later, as a Western invention that nobody understands and nobody needs to do anyway. Debates about relationships are dismissed as snowflake ideologies that don’t understand democracy. The mantra that “conceptual thinking is violent”, as the philosopher Petříček says, is a cover for anti-intellectualism, a conservative attitude that is sixty years old, the opinion of influential people without an argument. The sanctity of tacit knowledge leads to the branding of thinking as theory, theory as academicism, and with academicism being rejected for obvious reasons.

I’m a skin and it’s getting more and more empty inside. What kind of institutions do artists want? Or is it that they don’t want institutions, perhaps? Do they want lines of escape from the world, and then, abandoned by their own artistic experience, they negotiate the world and its political space with skills they could not take with them on the journey of aesthetic experience?

I’m not talking about all of them. And I’m not talking about the whole institution. Many create, teach and act so that life can flow again and others can fit in it. And indeed, yes, it is clear to me that aesthetic experience does not overlap with political reality. I’m not so naive as to think that artists are more politically refined than the rest of the population just because they experience art more often. Yes, the work of art has autonomy and thus exerts its own power separate from the artist. But now, actually, watch out. It has an autonomy and a power of its own that moves us. But where does it move us, and in what world? In an autonomous aesthetic experience? In a mindset of otherness that does not manifest itself in the physical body, in our life attitudes, in our everyday interactions, disconnected not only from the artist but from any actions in general? If art were of such an autonomous nature, it would be, as Blanchot says, so wonderfully free of the political as to be quite superfluous. How does art become a visual event that does not disconnect from our lives if we give up our belief in the causality of art and politics under the weight of experience? By what mechanism, by what catalyst, by what logic of the figurative, by what dynamics of the dreamlike does it move us?

The worst part is that the catalyst exists, it’s just obscure. My body walks the two hundred metres from DAMU to the Municipal Library by itself. Maybe it is walking on purpose, it is in a hurry to get some energy somewhere, and I say to it in approval: go ahead, I will try to catch up with you. At the moment my body runs using its legs, I still sit slumped at my desk, replaying today’s argumentative exchanges. Then I force myself to get up, I can’t let my body get far away, what would it look like at the exhibition if it were standing there without me?

To get close to a landscape in which speech is both intentional and unintentional, to forms of reflection that I have only indirectly associated with any artists. Taken out of the context, in bliss. A state where there are no relationships as a temporary liberation, at least until it starts to hurt even more than before.

The first and big theme of the exhibition is in the opening hall. A text by Paul Valéry: “The eye and the hand, following a curve commenced, look for the charm in its continuation, and try to continue on to where it would be pleasing to both of them.” People around, but me with Valéry, you don’t have to talk anymore, I’ll make do, yes, thank you, no, that’ll do, thank you. Valéry is not a person, he is a reflection that presents itself as a composition. It’s a chart showing the passage through the exhibition. There is a space between the mind and the body that is neither an embodied mind nor a thinking body; it is a space that does not unite but liberates. I accept a play laid out by the quote, and a quote from The Visible and the Invisible joins it, which comes to my mind spontaneously from my memory: “What consciousness does not see, it does not see for fundamental reasons; what it does not see, it does not see precisely because it is consciousness. What it does not see is precisely that which prepares in it the vision of the other.” A blind spot. It’s contentless. It’s not a context, nobody wants to say anything about it. Merleau-Ponty then adds: “What remains in the dream of the chiasm?”, of the intertwining of body and soul, of the embodied mind? What remains of the tension that constitutes both sides of the relationship? It seems to be basically nothing and at the same time the absolute basis –Stiftung.

Valéry underlined a few words in his fragment: “following”, “charm” and “pleasing to both of them”. I’ll follow the charm, as in a dream, the foundation that will be pleasing to both of us, body and mind put out of control of things.

Valéry is the last artist with a signature, after that the gallery is just full of challengers, cut from history, society, and their own biographies. Don’t ask me. The possibility to let the other just look and let me just look. To leave the self-projection face in order to face the other work and a human. Surprisingly, it is not in the dialectic of the same and the other, in any hermeneutics and consensus, but in this “just looking” that the charm is the strongest. When my gaze does not return but only stares, I leave the communication unnoticed. No more self-understanding and self-correction in favour of the world or the figurative. I take a different approach to the question of non-unity of the self. It’s a calm, a relaxation, I implicitly nod to the fact that I will always contain something unexplainable, however, this unexplainable does not invite me to strive for explanation. Something that is not mine, it doesn’t say anything about me, it doesn’t relate to me.

Skip Merleau-Ponty in the tunnel, just skip him. The idea as a light projection intangibly occupying the boundary between rooms, stopped by the resistance of the floor, made visible as a reflection in matter, a fragment sticking out, so as not to say that it occupies the space, that it perhaps, for God’s sake, interprets, that it thinks something. Okay. I understand: The ideas in this exhibition will be driven into the space of transitions, shifts, interstices, walls, places normally sensorially ignored, and in these extreme limits of visibility they will be able to attack by the sharp contours of paradoxes like fresh spikes of elusiveness. Why not just accept it?

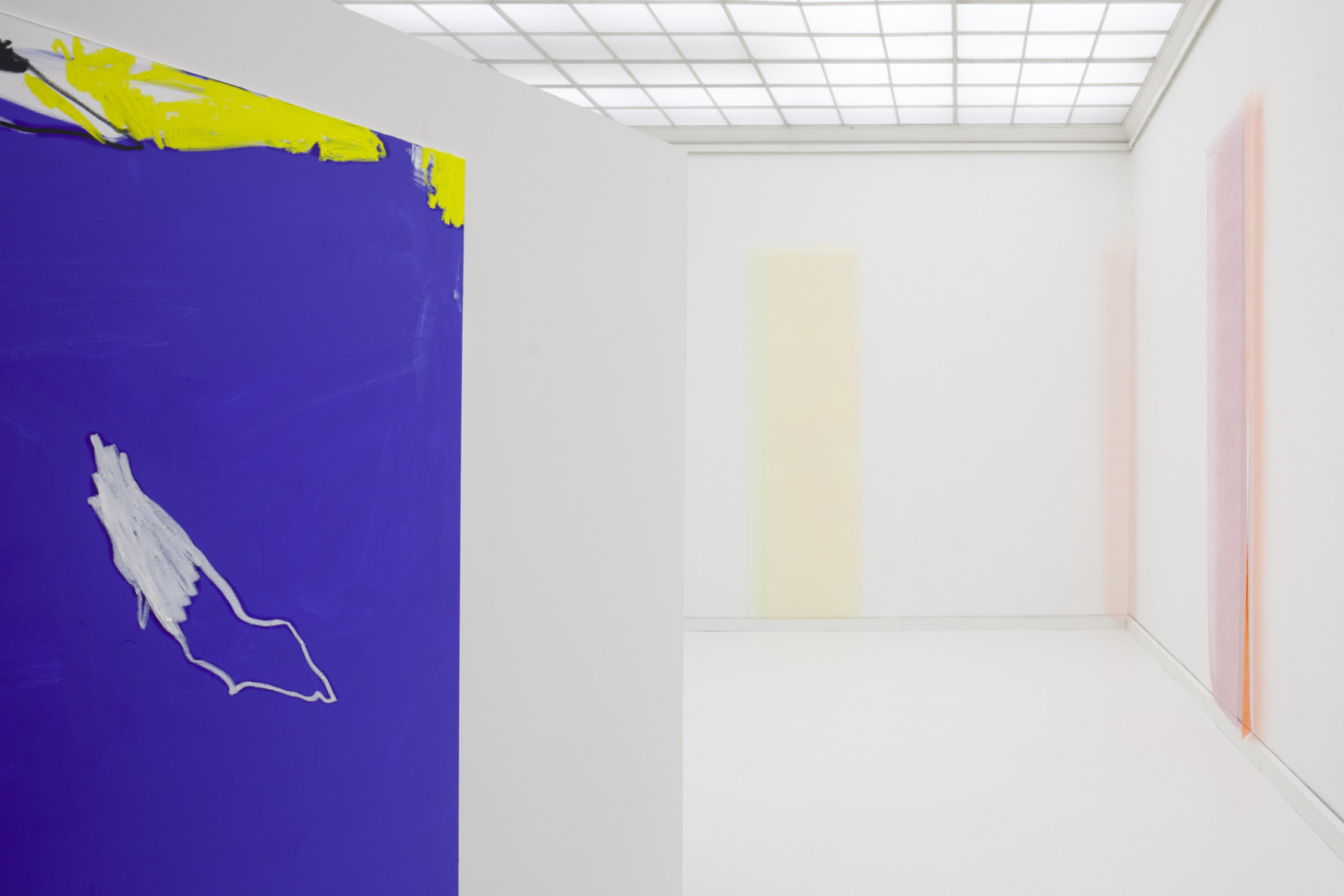

Room one. A volcanic explosion glowing along its inner boundary. Life begins in a fissure. It’s pushing outward, what is alive is always primarily the edge, not what defines. The burning contour exists as an extinction, the extinction of what surrounds, it grows to the places where it burns out, let us watch it carefully. To endure burning at the edges of oneself is to exist. To exist in the sense of ceasing to exist in a power that cannot be questioned. When the fire runs out, a new joy begins from the middle. A thing is where its highest heat reaches.

And the tunnel again. Skip Maldiney. I can’t do it, I must pass through him, pass through his projected luminous thought, I loathe it extremely, it’s impossible not to pass through him, what the hell kind of freedom is this, but at least when I pass through, I interrupt his reflection, his message, and offer him to be reflected on my surface, which brutally deforms the thought to the point of absolute illegibility. Resistance to representation is possible as a persistence in its dynamics, a takeover and deformation. I leave the darkness, and from the ceiling of the over-lighted space the skins peeled off of colourful whales hang in front of me.

Second room. They’re not whales, but they are whales. I bear witness to their past surfaces by swimming among them, by putting them on (no one is looking), by becoming what I never was and never will be, who would ever think I was a whale, but perhaps now I am, through witnessing, through the clothing. A visitor, someone I don’t know, comes to me and says something to me, but right now I’m a fish, I gawk my existence onto him, he responds, I would never have thought of that in my life, and then he quickly leaves, is disappointed, I have no way how to agree with him.

Reincarnation. Reframing, a room within a room. A space of a rhythm that never repeats. There’s music but no chorus. No return, no past, no flexion, just a plot that is endless. A singularity of no return carried by the scaffolding of the outer square structure, a white and invisible guarantee that the unrepeatability will remain something that will not be lost to itself. Anyone who can’t stand it, please leave through the door, there are two options, entrance and exit, a completely conservative arrangement, anyone who doesn’t want to participate, please exit through the exit, here, it looks like a door and it is a door.

Whoever walks out the door on the left encounters something that is complete only if it is completed by himself, that is, by the one who has just come, by the one who is observing and at the same time will play in it in that moment. The void constituted by the three fullnesses yawns aggressively, waiting to be filled by the incoming visitor, so that the whole can be realized and there is something to look at. It’s an outrageous request, but I’m agreeing to it for our mutual enjoyment, I committed to it at the beginning of the game after all. The end of the fragment, harmony wins, I am part of what I observe and without me there would be no harmony, without me there would be no work, with me it is complete, do you see with your permission that I “follow” “charm”?

Third room and fourth room. What was on display in the second room is transferred to the fourth room. One can choose either to see or to mediate, one cannot do both at the same time, the medium is not the message, the medium is the medium and the message is the message, whoever wants both crosses over or returns, anyway, without effort and without frustration one cannot get around, hopefully what is here is pleasing at least to someone.

Third room between the second and the fourth. Two pictures which look like dark coloured squares, only start to express their own nature when I take their photo. I forbid myself to interpret, I prefer to look into their darkness a little longer. This picture is a sensory perception that, even if I wait for a long time, gives me nothing. Say it with a photo, I make a proposal to the picture. It insists on hiddenness, a photograph will make an encounter impossible and allow the experience of seeing.

A flat man. I sit by him, I stand by him, I comeback to him. One can’t help but feel something very vague, something like precision, this is how it is, it is exactly like this. But it is not clear what it is that is this accurate. The flat man is another act and pure sensory invective, if people weren’t walking around I’d lie down next to him and flatten myself. Flatten yourself in bed. Waiting with a layered head crawling on the wall, without a mouth, looking out from it at those who walk around in the gallery as if in low spirits, unlike us flat people, you wouldn’t believe how many layers we are stuffed with.

Fifth, sixth and seventh. Big leaps across many rooms, I lose concentration, I remember the flat guy, I don’t have the stamina to look at everything and I don’t want to, I come across penises filled with scented oils and crumpled plants, I don’t even want to guess what it’s supposed to mean, it’s not about meaning in this exhibition either, I can see how their lives are separated from each other by long distances, penises on principle don’t share their bodily fluids with each other, let alone solidarity, let alone anything like relationships, that much is known, but their contents are surprisingly the same and surprisingly they compete in this exhibition in how deeply one of them hangs down, who has ever seen it, they usually compete in something else.

A shaky mirror. I resist illustrative interpretation. I notice the wound in the glass, the only one that isn’t shaking. Is it your point, please, that our disruptions are the only source of fixed identity we retain in our lives? You meant that when I look at myself, nothing is certain but the blow that someone has dealt me and I have no way of letting go of it, it has remained as a firm support, I can always go back to it, it will never fail me, the blow will never fail us at all.

Maybe room eight. A series of repeating panels, they appear to be metal, but even that is a mistake, the painting is a canvas, read the manifesto on the back about what the artist will never overcome, mired in a reproductive artistic space in which to be original is to repeat, in which to get visible means to collaborate with the system that enslaves, a piece of nice news, as long as the author doesn’t want to reveal his name, but it’s in room nine that I first meet Miroslav Petříček, I tell him the series in the next room is really great and Mirek says, yes yes, that Baladrán, it’s beautiful. Everything has gone wrong, non-identity has become a signature, anonymity has been given a specific personal unique name, so that Zbyněk Baladrán is the one who has demonstrated that he is not and cannot be, and thus is unique.

I’m going back to Valéry in a roundabout way. Where is Miroslav Petříček in this exhibition about an identity that is not? Not a single quote, not a single work is “his”. Petříček as an invisible element that manifests itself in the composition of the exhibition, in contradictory events connected by corridors or partitions, Petříček the ground plan, all of it, without being confirmed and recorded as a whole, Petříček as a liberated grammatical constituent with maximum valence potential, tying to itself different elements without being tied to anything. He outwitted even Baladrán, even though Baladrán did a lot to be there and not to be there, but Petříček inadvertently denounced him, saying his name; that happens too.

Freedom from the system as the only possible form of happy existence. Not happy in the sense of gifted, but happy in the sense of unencumbered, unsubdued. Among all those “things” that somehow “are”, it is crucial to perceive those that cannot or do not possess a conceivable and graspable identity. For the graspable ones make us graspable and inject us into the totality of the closed world. It is therefore self-preserving to perceive facts that do not confirm us. They exist unpredictably. For example in such a way that they appear as irregular bonds of a dynamic set of relationships, as components to be subtracted from a series, as reflections of something that was never original, as tangles without a centre, as burning peripheries advancing outwards to extinction, as ironic schemes of different references, as traces of what is absent, as what is visible only through a medium that has taken us to another room through its mediation, or perhaps as the flat man.

It is the happiness of the sovereign, the one who decides the exception.

Uniqueness.

The bitterness of this happiness is the impossibility of returning to the institution more prepared than how one left. Any return from the position of this freedom is just a return with a bigger dose of nostalgia. Escape line strategies allow singularity, they allow the getting out of the environment that deprives one of freedom. But they don’t think about how they themselves are potentially depriving freedom in this way, how they are leaving political relations at the mercy of those who do not seek lines of escape in any sense of the word. The self-preserving gesture that takes us out into a figurativeness that does not confirm us gives up the possibility of being a gesture for other people. This ambivalence persists and is equally strong throughout art history. Whoever lives the world of relations, whoever identifies violence in it, whoever calls it violence and not unthinkable, loses sovereignty. They are bound.

What impact does thinking along the lines of escape have on the power to bear a world where we must think even if we don’t want to think in its destructive form. To watch the world as it unfolds, in its monotony, in its futility, in its imprisonment, in its malignity, in the solidarity of those who bear it.

The author is a philosopher and vice-dean of DAMU