Father of the Serbian Avant-Garde or Was ist Kunst? Jakub Král

The post-war art of the former Yugoslavia did not have a chance to build on the pre-war first avant-garde. The work of the Serbian artist Dragoljub Raša Todosijević (* 1945) works with modernist concepts and symbols of 20th century totalitarian thought. How does their reflection look, blurred by the fluidity of global development?

Looking at the Serbian avant-garde through the lens of the Central European avantgarde, such a title might seem provocative at the very least, especially when talking about an artist working in the second half of the twentieth century. However, during Todosijević’s studies at the Belgrade Academy of Fine Arts in the second half of the 1960s, the prevailing approaches in art education were completely non-progressive, not in the sense of socialist realism, but rather of formally late-modernist painting with ideological content related to the history of the construction of Yugoslavia. However progressive the then higher education environment there was in comparison to what existed in our country, it was highly selective in relation to historical influences. Post-war Yugoslav art had little chance to build on the pre-war first avant-garde, and moreover, the Belgrade Academy of Fine Arts was the central art school in the capital of the entire federation at the time, which gave it the lustre of being responsible for educating artists in the interests of the state.

For many years, the ideological violence artificially maintained by the tradition of late modernist painting gradually created a new form of state art – a kind of liberal socialist realism – and at the same time, made it impossible to come to terms with pre-war art through a more or less continuous connection with the first Yugoslav interwar avant-garde. It is worth mentioning here one of Todosijević’s most famous early works: a performance he created in the 1970s entitled Was ist Kunst? In this performance, he asks his assistant, his own wife, a single question: “Was ist Kunst?”, i.e., “what is art?”, while smearing black paint over her face with his hands. The diction and emphasis with which the question is asked, however, intensify during the performance, and the urgency of the question begins to resemble a police interrogation, which continues until the interrogator, i.e., the artist himself, loses his voice. The question thus becomes a reassertion of the avant-garde’s moral claim on the work of art, but under completely different political conditions. At the same time, it becomes a great challenge to and questioning of art. It is thus a paradox that at the moment the avant-garde comes into being, art is already different and only adopts the means that make it avant-garde.

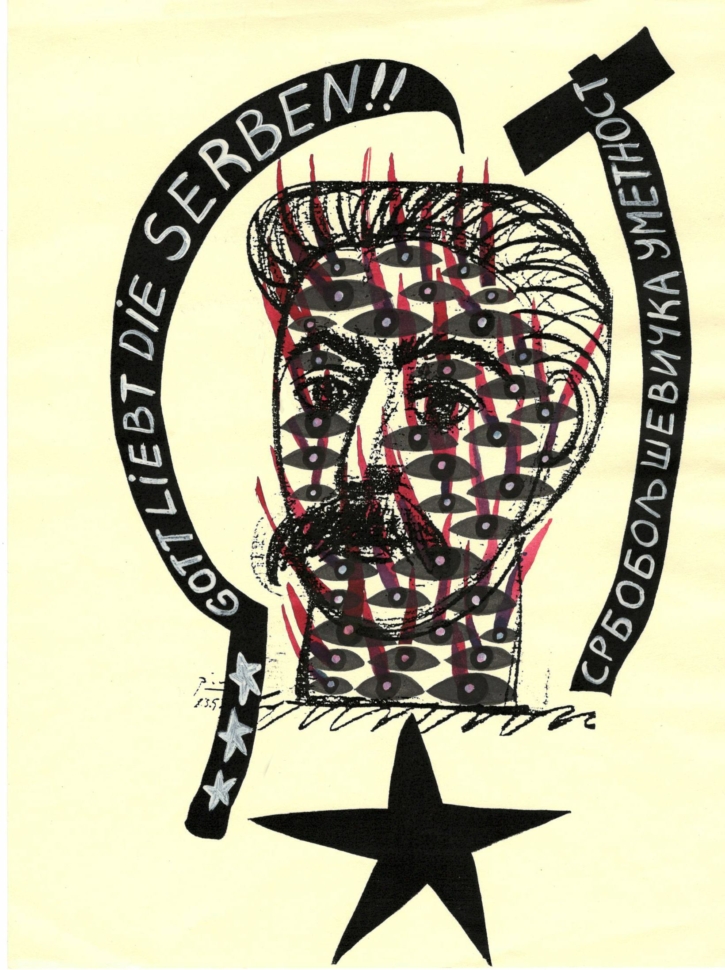

As a result of the constant challenge to art in Raša Todosijević’s practice and of the dramatic and drastic transformations of the world that he experiences and observes in his life, established symbols and their meanings have been fundamentally deflected in his thinking. The experience of the sheer fluidity of global development has blurred the lines of reading symbols in Raša’s work, as can be seen in the specific example of the swastika, which symbolises the totalitarian political thought of the first half of the twentieth century. But equally, this sign can also be one of the symbols representing pure modernism with its belief in progress, however much interpretative violence is involved. Either way, Todosijević, like other artistic groups originating from the region of former Yugoslavia, leaves us alone with our doubts about what such a symbol, taken out of context, can actually mean. It may well be that the exhibition will bring together diverse groups of visitors for whom this symbol will answer, each in a completely different way, the questions they pose to art, our world and our present.

The avant-gardist Todosijević, whose work adopts an avant-garde modernist form, is entirely postmodern, both intrinsically and in terms of his content. His work is therefore in a paradoxical situation and represents a specific transitional position. It replicates the world-changing rupture of the end of modernism and the manifold consequences of this end, which by far do not relate only to art itself; similarly, Raša’s art constantly oscillates between simultaneous affirmation and self-demolition.