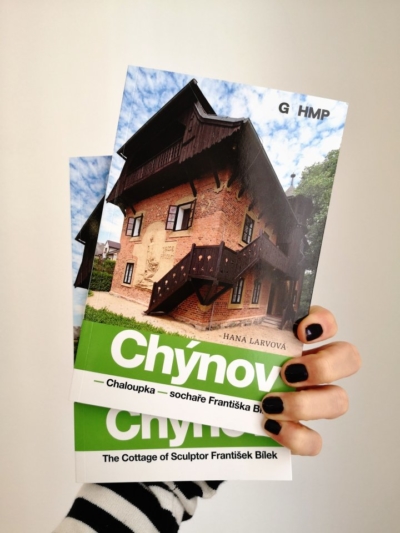

František Bílek’s Chýnov Visions

Address

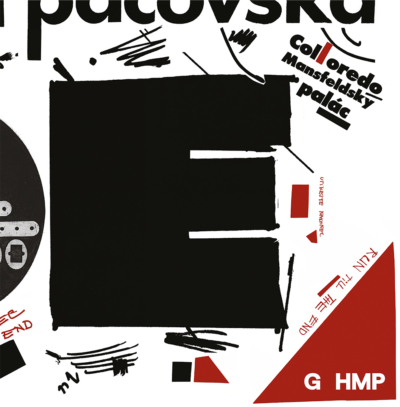

GHMP Bílkův dům

Údolní 133

391 55 Chýnov u Tábora

Map

The building is not barrier-free.

Download the audio guide to the birthplace of František Bílek and the Chýnov cemetery with his works. The guide with commentary by curator Martin Krummholz is in Czech and English and can be downloaded for free.

Open

Tue-Sun 10 am – 12 am, 1–5 pm

In the winter season from November 2, 2020 to April 30, 2021 only by telephone order (+420 774 204 388)

full 50 CZK

reduced 30 CZK

Curator: Hana Larvová

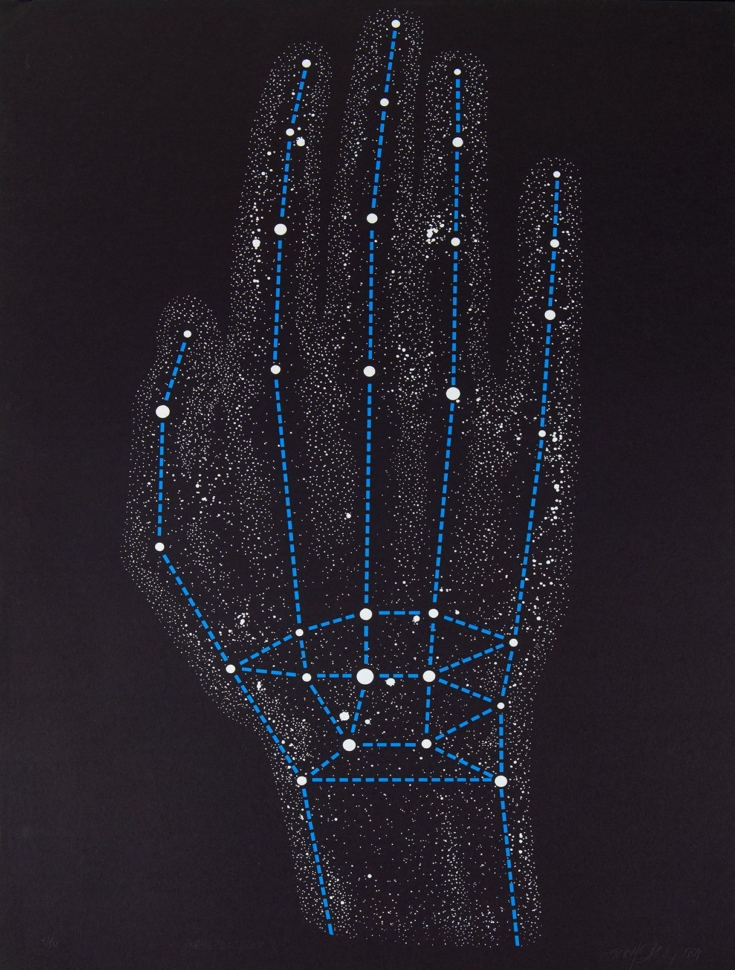

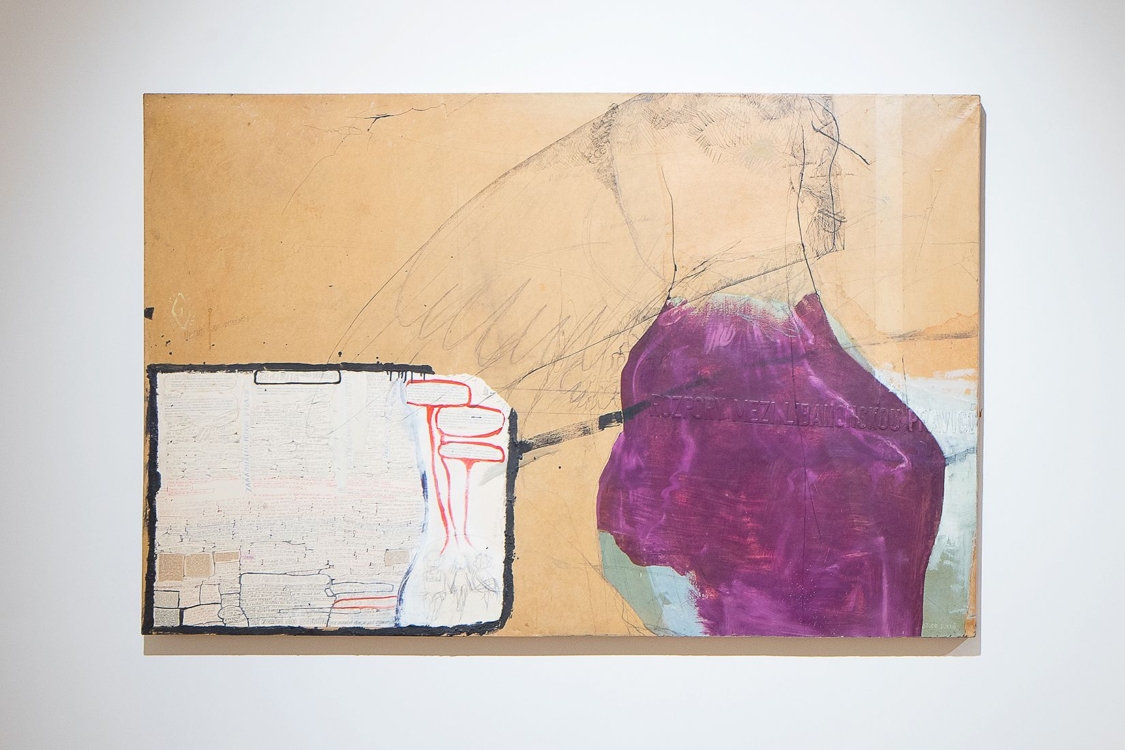

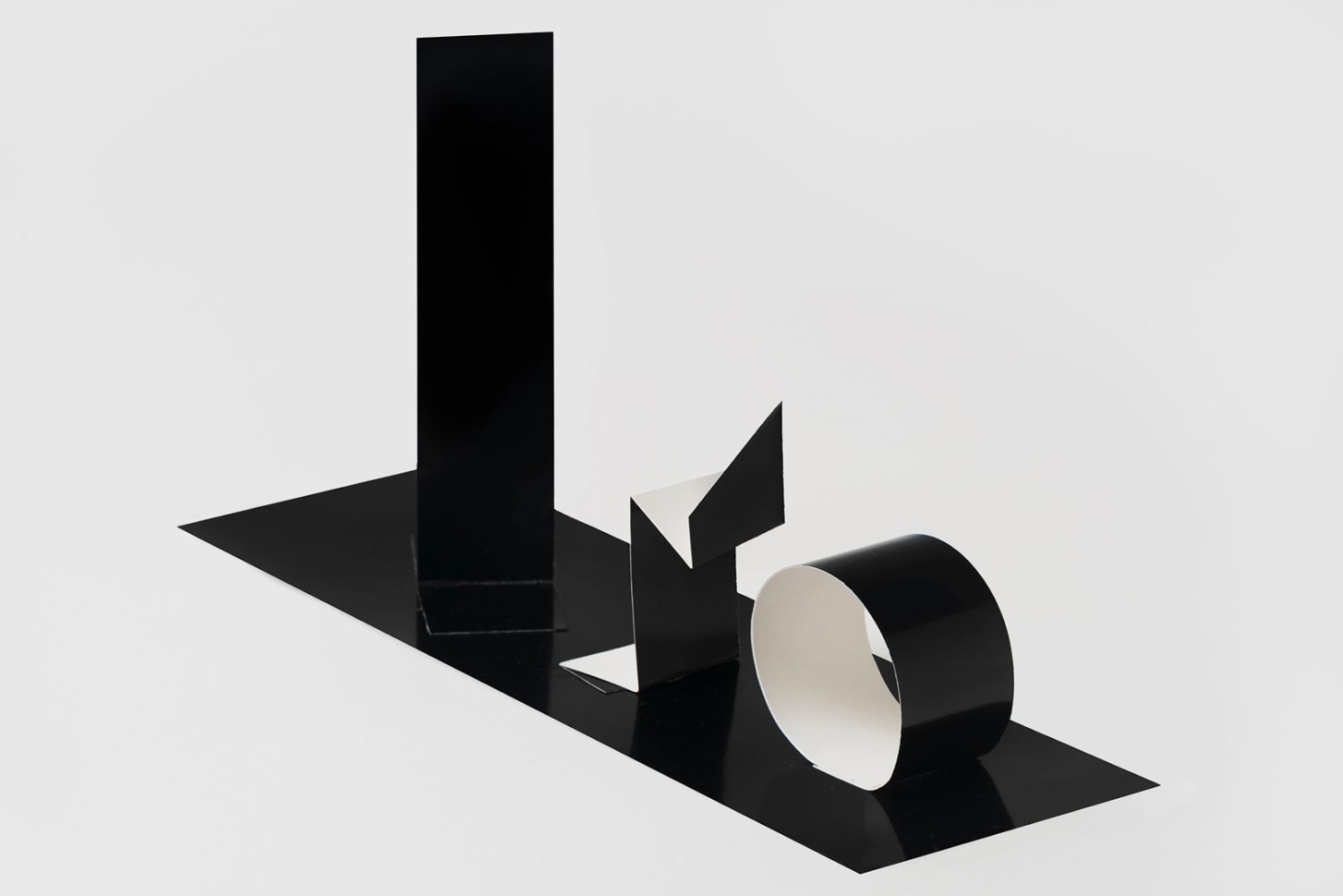

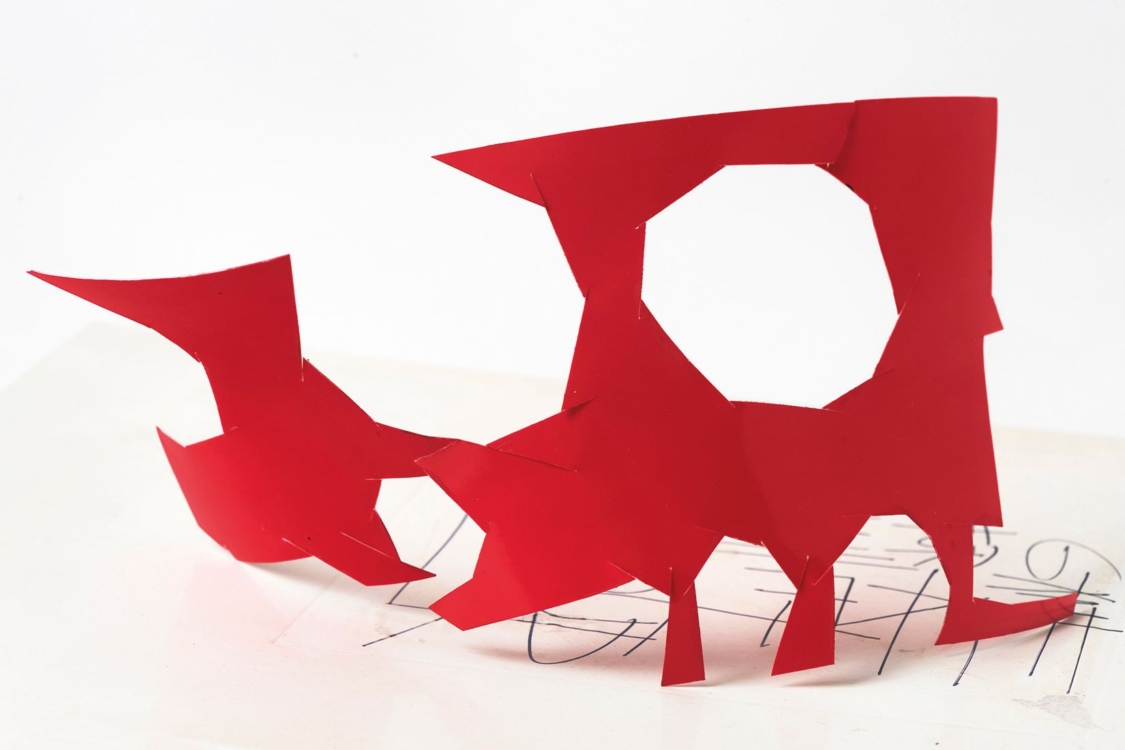

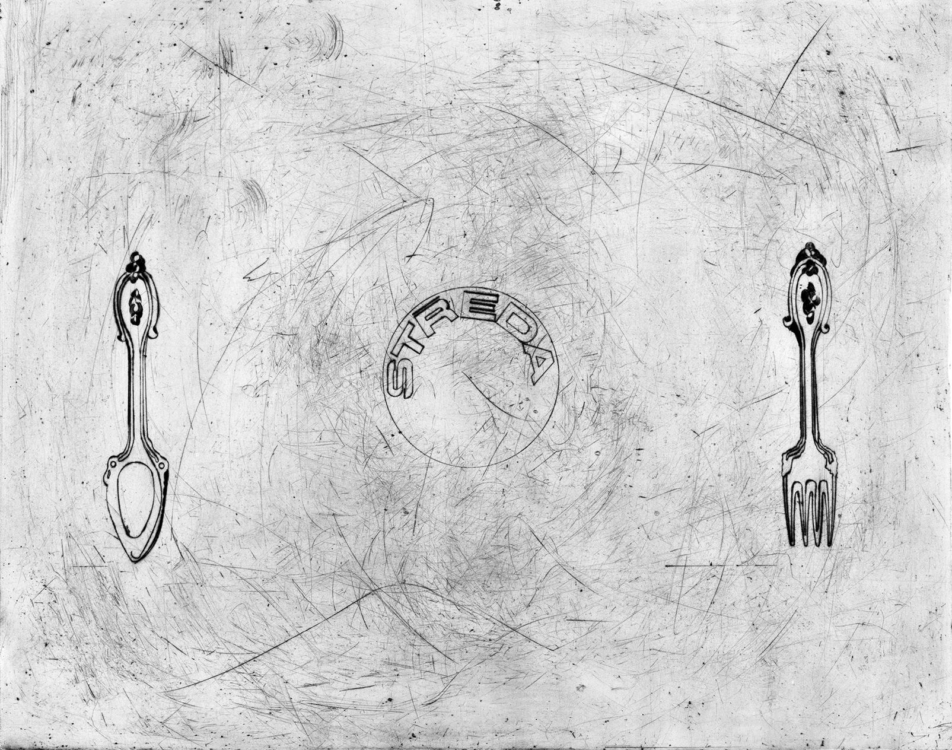

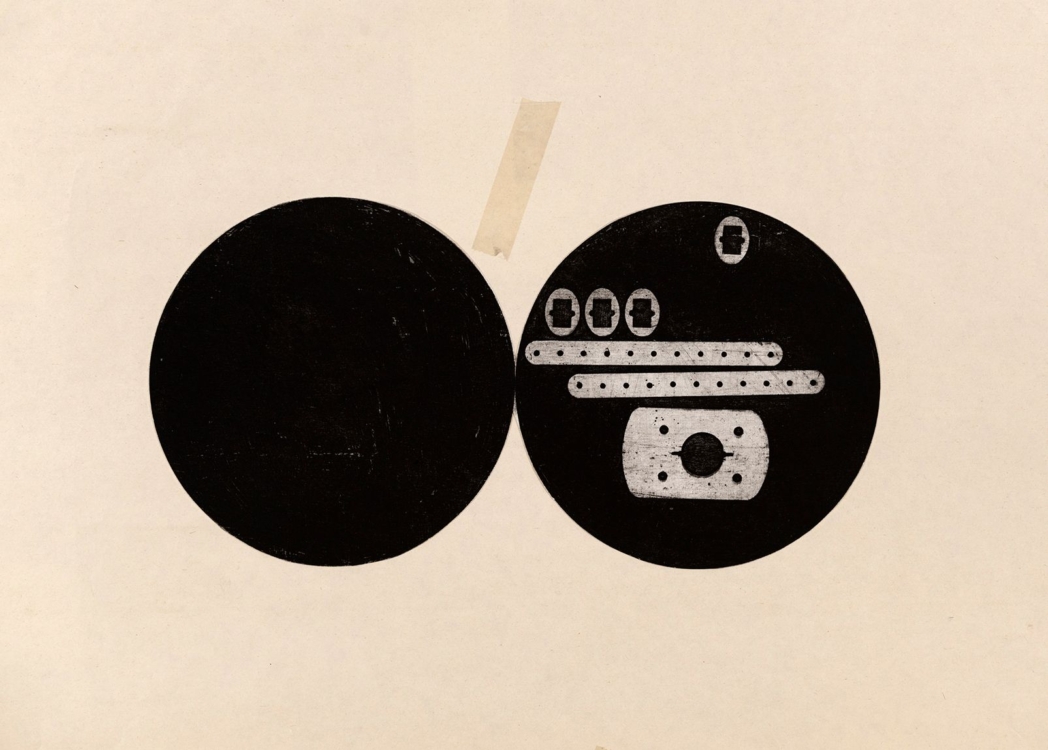

This exhibition presents you extraordinary Art Deco and Symbolist work of artist, which built in his native town Chýnov place for his activities in the form of individualistic variety of family house with the studio. The architecture of the house built by František Bílek in 1898 from raw brickwork with contemporary folkish wooden components and cuttings refers to the Chýnov traditional architecture. The representative selection of works represents artist mainly as a sculptor, includes also some samples of original furniture sets designed by Bílek for his daughter Berta and his son František Jaromír.

From the beginning of the 2020 season, František Bílek’s studio in Chýnov will present a small trailer for a long-term exhibition to be held on the 3rd floor of Villa Bílek in Prague in May 2021, which will focus on Bílek’s works inspired by his lifelong friend, the poet Otokar Březina.